Here’s a low-down of a rather wonderful Japanese games developer by the name of Sandlot. Officially formed in March of 2001, they approached the genre of mecha gaming with quite literally a new perspective.

Here’s a low-down of a rather wonderful Japanese games developer by the name of Sandlot. Officially formed in March of 2001, they approached the genre of mecha gaming with quite literally a new perspective.

In 1953 a budding manga artist, by the name of Mitsuteru Yokoyama, penned a series that would be responsible for laying the foundations of a pop-cultural phenomenon that has now lasted over half a century. The series involved a young boy remote controlling a giant robot by the name of Tetsujin 28-go (translated as Iron Man 28 and released abroad as Gigantor). This focus of the boy controlling a huge mecha from ground level was clearly an inspirational one in the case of Sandlot’s genesis.

For almost all but one of Sandlot’s games they have a very similar gameplay implementation in regards to the player viewpoint, that of a boy on the ground looking up at an immense mechanical behemoth (or at the very least a discernable sense of scale to the gaming proceedings).

It’s also interesting to note that this mechanical inspiration has consequently spawned a more successful series of games.

More after the jump:

Remote Control Dandy (PlayStation)

Technically this was made pre-Sandlot, in 1999, for the now defunct Human. The game was based around the player controlling a large mecha limb by limb from a fixed viewpoint on the ground. As a consequence, the player toggled between their human player and the mecha (allowing the former to get a better viewpoint on the resultant robotic carnage).

Technically this was made pre-Sandlot, in 1999, for the now defunct Human. The game was based around the player controlling a large mecha limb by limb from a fixed viewpoint on the ground. As a consequence, the player toggled between their human player and the mecha (allowing the former to get a better viewpoint on the resultant robotic carnage).

It’s worth explaining here what controlling a mecha limb by limb actually entails. The shoulder buttons represent the left and right leg respectively. In that pressing L1 and R1 sequentially makes the mecha walk by moving it’s left leg forward followed by its right leg. Conversely L2 and R2 make your mecha walk backwards. In the case of Dandy, arms are controlled via the face buttons Circle and Square respectively. Taking out a target requires the player to basically punch the crap out of it.

Due to the limitations of the original PlayStation pad, the game only let you control one thing at a time. In that, you had to toggle control between the mecha and the human viewpoint. This meant the human protagonist’s job was to get the best vantage point on the situation so that the mecha could tackle their target with greater clarity and ease. Understandably, the learning curve for the controls was pretty steep but surprisingly tactile nonetheless.

Dandy was the first game ever to try something like this in terms of mecha gaming and it worked really well. This was never released outside of Japan though and is only really recommended to the hardier brand of importers, well those that don’t mind PlayStation era graphics at least.

Tekkouki Mikazuki: Trial Edition (PlayStation 2)

To tie in with a 6 part live action mini series based around the majestic Mikazuki, this game was released with the first pressing of the original soundtrack and is quite hard to get now (to put it mildly).

To tie in with a 6 part live action mini series based around the majestic Mikazuki, this game was released with the first pressing of the original soundtrack and is quite hard to get now (to put it mildly).

The show told the story of Kazeo, a young boy whose life was saved by the appearance of a giant robot called Mikazuki during a monster attack. When it was discovered that Kazeo had the unique ability to pilot the robot in battle, he became a member of the AIT team. AIT was dedicated to protecting the Earth from Idea-Monsters (Idom). These creatures were the manifestations of people’s thoughts, and often appeared in unthreatening (even humorous) forms before transforming into vicious monsters.

This was very similar to Remote Control Dandy in terms of its gameplay approach but more simplified in terms of limb control and attacks. Though, more importantly, this was the tech that Sandlot prototyped for use on their other PlayStation 2 games.

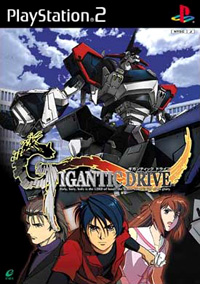

Gigantic Drive (PlayStation 2)

The first official Sandlot game and the one that got released abroad as Robotic Alchemic Drive. To all intents and purposes, this was Remote Control Dandy deluxe. The game focused on controlling each limb of your mecha from a fixed viewpoint, much like Dandy. The tech that had been prototyped on Mikazuki was taken further with Gigantic Drive. In addition to your bog standard skyscraper sized mecha, two of three available robots actually transformed too (one into huge tank and the other a futuristic war plane).

The first official Sandlot game and the one that got released abroad as Robotic Alchemic Drive. To all intents and purposes, this was Remote Control Dandy deluxe. The game focused on controlling each limb of your mecha from a fixed viewpoint, much like Dandy. The tech that had been prototyped on Mikazuki was taken further with Gigantic Drive. In addition to your bog standard skyscraper sized mecha, two of three available robots actually transformed too (one into huge tank and the other a futuristic war plane).

The biggest change over Dandy and Mikazuki was that the arms for each of the mecha were controlled via the left and right anologue sticks respectively. This resulted in the game really feeling like a mechanical puppet show; not to mention mastering punches, jabs and uppercuts was a more demanding affair than simply pressing a single button (a la Dandy).

Gigantic Drive also introduced the ability to have the human characters attack one another, rather than just getting stepped on by their mechanical avatars. This produced some interesting instances where finding the other player in multiplayer meant securing an easier win (after all if you took them out with a well placed grenade they wouldn’t be able to control their mecha).

I, personally, have many fond memories associated with this game. When I was living in Japan, local kids used to come over and play games. Gigantic Drive consequently got lots of versus playtime and several vocal victory dances (by the kids, not me).

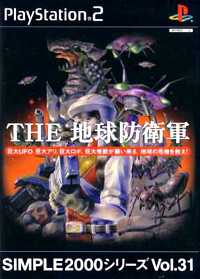

The Chikyuu Boueigun (PlayStation 2)

For those not familiar with Japanese publishers D3, they’re one of the main forces in budget gaming in Japan. Releasing games for around 2,000 yen a pop they offer affordable gaming to the casual masses.

For those not familiar with Japanese publishers D3, they’re one of the main forces in budget gaming in Japan. Releasing games for around 2,000 yen a pop they offer affordable gaming to the casual masses.

D3 approached Sandlot off the back of Gigantic Drive to make a game with the same engine. What D3 got was a game where the player controlled a tiny human protagonist taking on vertically endowed aliens. In English, you tore giant alien ants a new one with rocket launchers in a massive destructible environment.

Admittedly, this wasn’t a mecha game per se (though it did feature a mecha Godzilla clone and huge alien tripods) but The Chikyuu Boueigun wouldn’t have been created without Sandlot’s previous mecha gaming outings. In many ways, their fascination with the scale of mecha and the mythos surrounding them crystallised a new and vastly satisfying third person action game.

In addition to the gun toting action, the player could also mount a nippy (but vulnerable) air bike, a tank and a helicopter (though the latter was notoriously tricky to handle). If that weren’t enough, each of the game’s single player missions could be played in two player co-operative multiplayer. For the price, the game was an unbelievable gem and it sold well as a consequence.

The Chikyuu Boueigun was released abroad as Monster Attack and garnered quite a following, to the point that several sequels have been spawned (though more of that later).

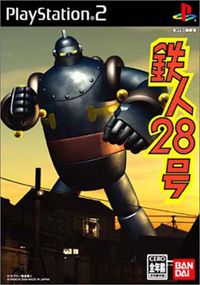

Tetsujin 28-go (PlayStation 2)

Following on from the success of The Chikyuu Boueigun, Bandai approached Sandlot with a chance to create a game to tie-in into the new Tetsujin 28-go re-make.

Following on from the success of The Chikyuu Boueigun, Bandai approached Sandlot with a chance to create a game to tie-in into the new Tetsujin 28-go re-make.

In many ways, having Sandlot make a game that started the mecha genre in Japan and more pertinently Sandlot’s focus on scale centric gameplay was almost prophetic.

The game was great though; similar to Gigantic Drive in approach but with a simplified set of controls for the arms (you only used the Dual Shock 2’s face buttons rather than the anologue sticks, which was more akin to Dandy than Gigantic Drive) but this produced a more focused and rhythmic pace to the combat. Something the smaller scale mecha were more suited towards.

The game also made more of an effort to model flight for each of the mecha. In addition, it was possible to have the mecha pick up their human controllers and negate the need to find the best viewpoint for the action. Tetsujin 28-go also offered some pretty raucous four player versus action.

Unfortunately, this never made it outside of Japan (despite the re-animated TV series making it abroad). Though the more poignant aspect of this game’s release was that Mitsuteru Yokoyama died earlier in the year, never getting to see his formative work in gameplay form.

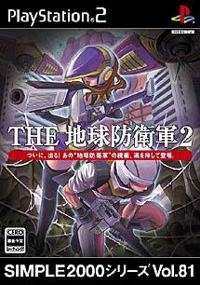

The Chikyuu Boueigun 2 (PlayStation 2)

Despite the success of Tetsujin 28-go, Sandlot once again returned to the world of giant alien ants and huge alien motherships. In many ways the sequel was literally twice the size of the first game.

Despite the success of Tetsujin 28-go, Sandlot once again returned to the world of giant alien ants and huge alien motherships. In many ways the sequel was literally twice the size of the first game.

You now had two playable characters; the default vehicularly capable man and a new aerially competent woman. The game also sported nearly triple the number of missions from the previous game. Considering that this was a budget title, the amount of top notch gaming available puts many full-blown productions to shame (plus it started out in London, with giant aliens crawling all over the Houses of Parliament, which clearly makes it amazing).

Again, whilst technically not a mecha game (though it did feature more mechanical alien vessels this time around) the game clearly came from a honed understanding of how scale in mecha gaming is so important in relation to how the action is portrayed (as in suitably epic).

Some of the missions in the game were immense in scope and whilst the framerate often went on the fritz, the sheer immense undertaking was mightily impressive fun.

This also received a limited Western release, under the moniker of the Global Defence Force, and garnered an even greater following than the previous game.

Chousoujou Mecha MG (Nintendo DS)

Up and till this game, Sandlot had focused on producing epic scale in gaming form. Considering the technical limitations of the Nintendo DS in this department, Sandlot turned their attention towards the platform’s unique touchscreen control setup.

Up and till this game, Sandlot had focused on producing epic scale in gaming form. Considering the technical limitations of the Nintendo DS in this department, Sandlot turned their attention towards the platform’s unique touchscreen control setup.

In many ways, Mecha MG is a brave title. Instead of having the player on ground level looking up at a huge robot as well as having to reposition themselves for the best vantage point, they are instead placed directly behind their mecha but afforded a more complex control system on the touchscreen. To make matters more varied, each of the 100 mecha in the game sport totally different controls and gameplay attributes.

Unlike their previous games, where controlling a weighty mecha is meant to feel cumbersome, the controls in Mecha MG leave a little to be desired. In that, having multiple points of control clustered in close proximity with one another can often produce undesirable consequences (as in accidentally transforming your mecha into a roadster rather than swinging its arms). Admittedly, as with all games, this is part of the learning curve but in the case of the Remote Control Dandy lineage the deliberate movements made the game more tactical and afforded greater clarity to the controls, Mecha MG’s controls are subsequently more immediate and a little messy in contrast (to begin with at least).

This is not to say that Mecha MG isn’t a huge amount of fun and unlocking various new mecha and getting to play around with them is a huge draw (after all you want to know what crazy whacked out control system the game will throw at you next).

At present, this has only been given a Japanese release though with the Nintendo DS’ global success and the public’s desire for quirky titles, Mecha MG may get a Western release sometime soon.

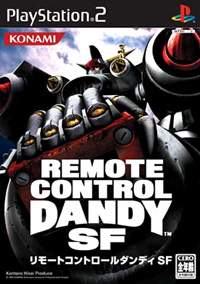

Remote Control Dandy SF (PlayStation 2)

Meant as a sequel to the original Remote Control Dandy on the PlayStation, SF took the premise further by possibly having the most complex control system ever attempted on the Dual Shock 2.

Meant as a sequel to the original Remote Control Dandy on the PlayStation, SF took the premise further by possibly having the most complex control system ever attempted on the Dual Shock 2.

Much like the original game, the player controls a large mecha limb by limb from ground level. The main difference over the games before it is that SF allows the player to control both the mecha and human commander simultaneously.

In that, you can move your viewpoint at the same time as moving each limb of your mecha. It takes a little getting used to but once mastered in makes the previous games feel quite constricted.

The reason I haven’t included this in the timeline above, is that technically it may not be a Sandlot game. True, it bears the same name as proto-Sandlot’s flagship game as well as many of the hallmarks of Sandlot’s scale based control. Yet, the game’s credits lack a mention of the company and more tellingly Sandlot’s online portfolio does not list SF at all.

Whether or not Sandlot worked on SF, it’s an excellent game that evolves Sandlot’s various opuses to the point it felt as though it should have always been thus. Plus, the name alone denotes a heritage that needs to be acknowledged.

Again, SF lacked a Western release. This obviously being a shame because the mecha design by Kow Yokoyama and the retro-stylings of the game’s visuals are pretty damn impressive, not to mention the fluidity of the gameplay.

…time to put that robot to bed

What with another Chikyuu Boueigun game around the corner (now on the Xbox 360 no less) and a Chikyuu Boeigun strategy game already out, Sandlot clearly have grown out of their mechanical pastures for the time being. Mecha MG showed that the company could tackle different design approaches with their vibrant mecha based enthusiasm, so with any luck we may see a similar effort on the Wii (with whacked out controls to match).

Whilst you often hear then term “sandbox” in regards to gaming, Sandlot’s approach is arguably the Japanese equivalent. Huge destructible environments for the player to roam within (either with a mecha by their side or just with a trusty rocket launcher).

The interesting thing about Sandlot is that their unique approach to mecha gaming has had knock-on effects to the design of other genres, most notably that of action games, and there was me thinking that mecha could only destroy things.

I’m a big fan of Macross and I think that franchise should receive the humunguous mecha reality sandbox treatment also.

[…] An Ode to Sandlot “The interesting thing about Sandlot is that their unique approach to mecha gaming has had […]